The 4 Factors of a Fulfilling Life: Psychologically Proven Ways of Cultivating Well-Being

Harmonizing Purpose and Practice: A Guide to Discovering Your Ikigai and Living Mindfully

1. Discovering Your Ikigai

Your ikigai is your reason for getting up in the morning, your “reason for living.” It’s a Japanese term that’s been mentioned in plenty of psychological life-improvement content, including Neil Pasricha’s bestseller The Happiness Equation (a great read, by the way). Your ikigai is your “ultimate why,” your meaning in life, so to speak. Your ikigai statement should connect with you on a deep, emotional level. The goal is to embed your ikigai into every moment of your waking life, whether you’re brushing your teeth, at work, paying your taxes, or eating dinner with your family. Reminding yourself of your ikigai each day can give you a big boost of motivation to get you past ruts and remind you of the things that really matter.

To find your ikigai, probe yourself for your “ultimate why” until you reach a definitive, indisputable reason for you to conduct your life as it aligns with your greater purpose. Additionally, reflect on activities that you seemingly gravitate to without much thought, something that you return to almost habitually. What are you seeking from it? Try imagining your life without this activity. Does anything feel missing? If it does, ask yourself why, and try to find ways to further integrate it into other areas of your daily life.

If you align with a particular religion or philosophy, ensure you connect with it on a deep level. For some people, their religion is an inseperable part of their ultimate why. However, don’t subscribe to the belief simply because you feel pressured to do so or even because it appears logically sound. Your system of choice should produce wise, compassionate people, and should be in harmony with your ikigai. Wise people have experiential knowledge of what produces happiness and leads to unhappiness. They use compassion to show others this wisdom and bring others to happiness. In searching for a belief system that emphasizes these qualities, you should seek to be like these superb people, whether it’s Jesus, the Buddha, or whomever. Be curious and experiment with these frameworks!

Continuing with this theme, be prepared to ask skeptical questions so you can eventually feel a faithful conviction in your belief system. Otherwise, your sense of purpose will rest on a house of cards and will feel empty. If your religious or philosophical beliefs don’t seem to agree with your ikigai, try to find out why this is. This belief system, in conjunction with your ikigai statement, should provide you with an all-encompassing framework for how you should conduct your life. If your life, ikigai, or belief system are in disagreement with each other, something will feel wrong (i.e. a feeling of dissatisfaction or dissonance). Similarly, if these three things don’t instill some feeling of motivation, happiness, or excitement, consider re-evaluating your alignment with them. Can you really see yourself abiding by these frameworks for the rest of your life?

Reminding yourself of your ikigai every day is especially important. This can be as simple as hanging a post-it note on your bathroom mirror so you inevitably see it as you start the day. Your ikigai should seep into every aspect of your daily life. For example, my ikigai entails developing mindful activity and compassion toward others. Every few minutes, I will check in with myself and ask if I’m abiding in the present moment. If I find myself in a conversation, I ensure I’m mindful of what I’m going to say so that I don’t say something harmful or unnecessary. If I notice anger arising, I close my eyes and take a few breaths, and try to understand the other person’s perspective and if I did anything to hurt them. Little activities like this, regardless of how small, continually reinforce your ikigai and can produce great feelings of fulfillment.

2. The “Wills and Won’ts”

Now that you’ve found your ikigai, you need to settle on a moral framework. Dedicate some time to decide on your “wills and won’ts,” (creative, I know) preferably writing them down as a list somewhere. The name is pretty self-explanatory: the goal is to commit to performing your wills every day, while avoiding performing the won’ts.

Once you’ve decided on your wills and wont’s, write down a statement to repeat at the start of every day so you can commit to your wills and won’ts. For example: “I, [your name], will do my utmost to uphold the principles outlined on this list so that I may [ikigai statement (ex. “provide compassion to those around me”)]. Should I deviate from this framework, I will reflect upon the causes and appropriate solutions so that I may continue to bring happiness to myself and others.”

If you don’t follow through with your wills and won’ts, don’t beat yourself up! The goal isn’t to feel guilt, but to be more mindful of how your actions—those of the body, speech, and mind—condition your and others’ experiences.

3. Meaningful Work

Ensure you’ve chosen a livelihood that, again, aligns with your ikigai. Like the saying goes “if you love your job you never work a day in your life.” If this doesn’t seem possible, investigate ways you can embed elements of your ikigai into your work, or ways in which your job may indirectly relate to it. Some questions to ask yourself are:

“Why am I doing this?”

“Does this job allow me to follow my will’s and won’ts?”

“Do I feel any hint of guilt or regret by the time I finish my workday?”

Meaningful work should create a sense of fulfillment. Fulfillment, in one form, can come from getting closer to your goal(s). Ensure you’ve established a long-term goal to pursue and remind yourself of every day. At the very least, you shouldn’t feel heavy resistance when starting your workday (“Ugh, I really don’t want to go to the office today. Can’t I just take a sick day?”). If you do, then you need to do some introspection and ask yourself the reasons, and, if possible, resolve those issues. At the very best, however, your livelihood is fully aligned with your ikigai, and your goals, short term and long term, are attainable, and you therefore feel excited and/or motivated to start the day.

4. Mindfulness and Equanimity

Mindfulness is a moment-to-moment awareness of present internal and external apperances (material objects, sounds, thoughts, feelings, etc.). Combined with equanimity (a detached and relaxed sense of non-judgement of these appearances), these factors can help us make healthier choices, be more focused, and, perhaps most crucially, stop exaggerating our thoughts through the belief that they define our desires and motivations.

Training in mindfulness allows you to disrupt the chain of discursive thoughts—thoughts will very little gap between the next, almost continuing in a subtle stream—and therefore maintain awareness of the present moment. This can mitigate feelings of anxiety (worries of the future) and depression (regret and sorrow regarding the past) provided you’ve trained in equanimity.

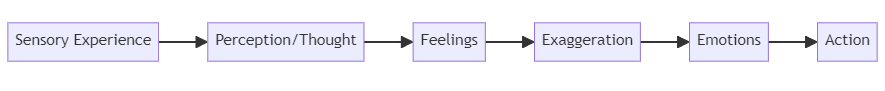

Some actions, like those that result from emotions, are produced like this:

Say you walk into a kitchen and smell a freshly-baked pan of cookies. The smell has made contact with your nostrils, which communicate that information to your brain’s olfactory structures. Mere fractions of a second pass between the sensory experience itself and mental perceptions, which allow you to recognize the smell as that of cookies (similar to how we communicate in sounds and not words; words are only recognized when our brains make sense of what we hear). Through these conceptualizations, your mind identifies this smell as a positive experience (something that smells delicious). You attach to and exaggerate these positive sensations, producing mental states that further conditions these feelings and leads to actions according to those mental states.

In this case, after feeling really good from smelling the cookies, you attach to this experience, and feel a sudden craving or longing for the future experience of eating the cookies. By identifying with this emotional craving, you’ve unknowingly relinquished control, and, a few seconds later, you find yourself with a chocolate stain on your shirt. Furthermore, even if you refuse to indulge your craving, chances are you’ve generated many discursive thoughts or emotions. Perhaps you’ve engaged in an internal battle or negotiation (“Oh man, I really want those cookies, but I need to lose some weight. But on the other hand, I’ve worked really hard today, so I deserve it.”). Or maybe you work up feelings of disgust or guilt. In doing so, you’ve substantiated, or “reifed” your perceptions. This may not matter now, but given time, much unneeded stress and anxiety can be built up and lead to irrational and possibly detrimental decisions. This is why calming down this overactive, clingy mind can feel so relieving and eye-opening.

If you’d like to engage in these types of practices, I’d encourage you to take a look at one of my other posts, where I take a deeper look at the neuroscience of meditation and instructions for getting started.

Concluding Thoughts

Don’t make the mistake of attempting to implement all of these solutions at once! Start small, perhaps by trying out one, seeing how it goes, and then gradually working toward another. Remember, it’s consistency and sustainability that matter with these solutions; introduce too many variables at once, and your motivation will inevitably dissipate.

The bulk of this post is aligned with the research ideas of Dr. Richard Davidson, one of the world’s leading researchers of emotion and the brain. In The Book of Joy, Douglas Abrams elaborates on some of Davidson’s findings by identifying four independent brain circuits identified with supporting long term well-being:

The ability to maintain positve mental states and emotions - one great way to start, as recommended by both Archbishop Desmond Tutu and the Dalai Lama, is by cultivating feelings of love and compassion toward others. This is why both your ikigai and productive, meaningful work is so beneficial.

The ability to recover from negative mental states and emotions - surprisingly, this circuit operates completely independently from the previous one. By finding your ikigai and training in mindfulness, it becomes much easier to identify and reframe these emotions such that recovery becomes almost second nature.

Very recently, my brand new $500 mountain bike was stolen as I was out of town. I walked up to the bike rack, fully expecting to see it there for my commute to the other side of my college campus, which is about a 25 minute walk away, only to see it missing. What did I do? I had a quick moment of shock…and then…acceptance. Nearly no anger, panic, or annoyance whatsoever. Afterward, I reported the bike stolen and went home without a fuss. No complaining to my roommate, exasperated phone calls to parents, or angry rants with friends. What good would any of that do? It’s just a bike.

The ability to focus and avoid mind-wandering - meditation, people.

The ability to be generous - yup, generosity can help you live a more fulfilling and happy life. Who knew? This is definitely one way your wills and won’ts can help you out here.

Too long? Here’s a bite-sized summary:

Finding Your Ikigai: Ikigai is your personal reason for being, deeply connected to your life's meaning. To discover it, deeply explore your "ultimate why" and activities that draw you in naturally. Align your ikigai with your daily life, ensuring it resonates emotionally. If you follow a religion or philosophy, it should harmonize with your ikigai and promote wisdom and compassion. Regularly question and reflect on your beliefs to ensure they strengthen your sense of purpose. Keep your ikigai in mind daily, integrating it into even the smallest actions.

Setting Your 'Wills and Won'ts': After identifying your ikigai, establish your moral framework by listing your daily 'wills' (positive actions) and 'won'ts' (actions to avoid). Begin each day by affirming your commitment to these principles, linking them to your ikigai. Remember, the aim is mindfulness and improvement, not guilt, if you sometimes deviate from these guidelines.

Choosing Meaningful Work: Ensure your job aligns with your ikigai. If there's a disconnect, find ways to incorporate elements of your ikigai into your work or understand how your job indirectly supports it. Your work should not evoke guilt or regret but should bring a sense of fulfillment and align with your long-term goals.

Practicing Mindfulness and Equanimity: Develop moment-to-moment awareness and a non-judgmental attitude towards your experiences. Mindfulness helps disrupt continuous thought patterns, reducing anxiety and depression. Recognize how attachment to experiences can lead to impulsive actions and stress. Training in mindfulness and equanimity offers clarity and better decision-making.

General Advice: Start with small steps, focusing on one aspect before moving to another. Consistency is key. The concepts align with Dr. Richard Davidson's research, emphasizing the importance of maintaining positive states, recovering from negative emotions, focusing, and being generous. Remember, your ikigai, moral framework, and mindfulness practices are tools for building a fulfilling, harmonious life.